Although much has been written on service recently in the wake of the Court of Appeal’s decision in Knight v Goulandris which dealt with service by e-mail under the Party Wall etc. Act 1996 (“the Act”), an interesting point on service also arose in the most recent instalment of the case between Mr Gray and Elite Town Management Ltd (“ETML”), the judgment in which can be found here.

It is possible that the genesis of this long-running dispute between neighbours in an attractive West London mews can be found in the appointment by ETML of a surveyor on Mr Gray’s behalf, under section 10(4) of the Act, a step rarely welcomed by an adjoining owner. ETML, the building owner, was planning a basement extension to its property at 9 Ennismore Mews (“9EM”). Mr Gray owned 7 Ennismore Mews (“7EM”) but did not live there, although he did visit the property periodically, as the director of ETML was aware.

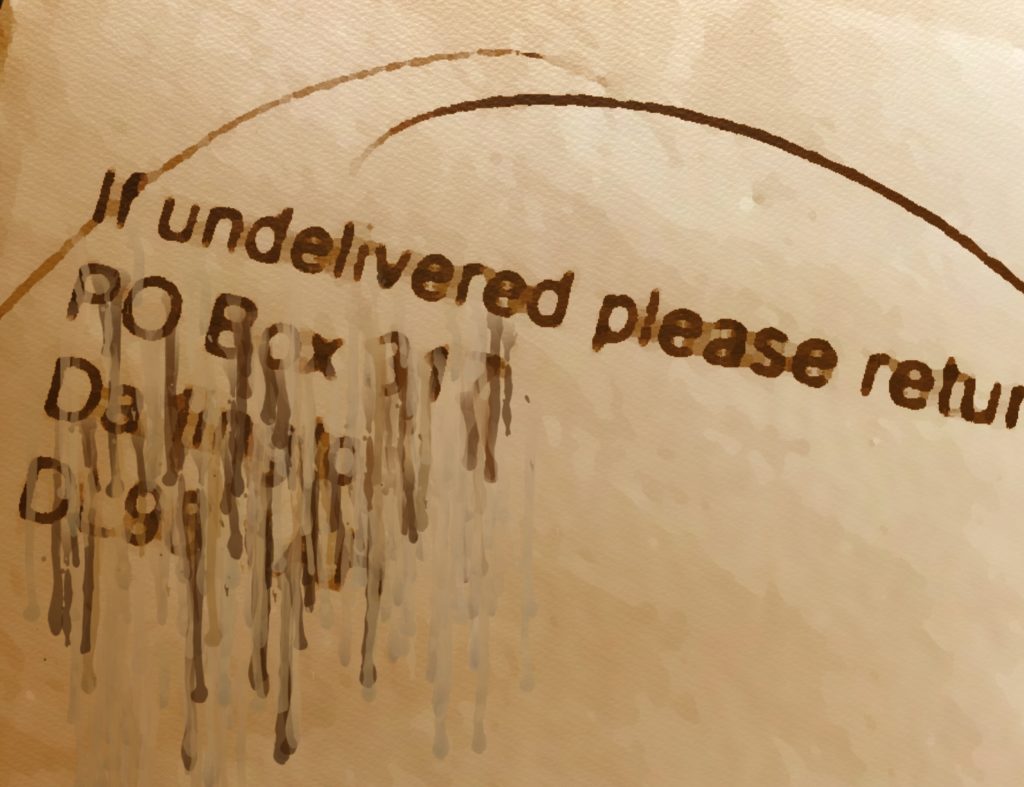

The party wall notices relating to ETML’s proposed works were not served at 7EM, but rather were sent to Mr Gray’s address as recorded on the Land Registry title for 7EM. As it turned out, Mr Gray did still own that property, but it was “empty and seldom visited at the time” the notice were served.

As the HHJ Bailey observed:

ETML’s actions were, probably, lawful under the 1996 Act by virtue of the provisions of s15(1)(b) which permits service “by sending it by post to him at his usual or last known residence or place of business in the United Kingdom”

However, the judge went on to say:

There have been many and bitter complaints of Mr Gray’s conduct by Mr Hill and ETML’s advisers, and these complaints are, in context, understandable. But ETML and its advisers (to the extent that the latter were involved) should accept a good measure of criticism for proceeding to appoint a party wall surveyor for Mr Gray in the circumstances outlined above without at least serving copies of the party wall notices at 7EM. It is after all well known that addresses at HM Land Registry which are other than the property itself not infrequently become out of date. Reliance on such an address as a “last-known residence” without also serving the property does give cause for concern.

One might be forgiven, on reading this, for thinking the judge’s comments a little harsh. Why should ETML face criticism for acting lawfully? After all, being conscious that 7EM was visited only occasionally, and having done a Land Registry search which provided an alternative address for Mr Gray, what was wrong with serving him at that address?

The answer is that whilst the notices may, as the judge noted, have complied with the requirements of section 15(1)(b) in terms of serving it at the last known residence or place of businesss – although I note that there does not appear to have been any enquiry into or determination of whether the address used for service was in fact either of those things – there does not appear to have been any genuine effort to bring the notices to the attention of Mr Gray.

It seems to me that there are two lessons to be learnt from this example, one procedural/practical, and one rather more psychological:

(1) If there is any doubt as to where notices or other documents should be served – for example where the adjoining property is unoccupied – spend a few minutes researching what address or addresses might be current. Of course it is a good idea to do a Land Registry search in every case, since this is necessary to identify the correct owner in any event, but do not simply assume the address given for the owner which appears in the Land Registry proprietorship register is the correct or current address. Often such addresses are merely the address where the proprietor was living when the adjoining property was purchased. A short internet search is often all that is necessary, and you may well be able to obtain an e-mail address from the building owner in any event. If in any doubt as to which address is the correct address, send the relevant notice or document to all of the candidates for the correct address. Remember that the essence of service of a document is receipt of that document by the intended recipient. Better that they receive five copies of the notice than none.

(2) Many of the party wall and boundary cases which come to me as litigious disputes have their beginnings in poor communication. Neighbours are unlikely to welcome building works next door at the best of times; if the building owner fails to communicate his intentions clearly and at the earliest opportunity to the adjoining owner, opportunities for conflict quickly arise. It is difficult to think of a situation more likely to give rise to suspicion of a neighbour’s motives and intentions than to “serve” a notice on a property which is unoccupied or likely to be a historic address. In fact, it does strike me that, in the Gray case, even if ETML had served notices on 7EM as well – as the judge suggested they should have – it is quite possible that they would not have come to Mr Gray’s attention for some time. However, if ETML had made an effort to actually communicate its intentions to Mr Gray, not only via the formalities of party wall notices, but, ahead of such notices, in an informal but informative way, it is possible, I would like to think, that ETML could have built its basement extension without the parties having to resort to the courts to resolve their differences.

Nick, thank you for bringing this aspect of Gary v ETML to everyones attention. I concur wholeheartedly with your final paragraph (2) and, in principal, with paragraph (1). However, I am surprised that HHJ Bailey did not refer to the Appeal Court case Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council v Tanna [2017] which would suggest that ETML’s actions were very much lawful and not ‘probably lawful’ as His Honour surmises. The following statement by Lord Justice Lewison is especially pertinent.

“I would hold that as a general rule, unless there is a statutory requirement to the contrary, in a case in which:

i) a person (in this case the local planning authority rather than the council taken as a whole) wishes to serve notice relating to a particular property on the owner of that property, and

ii) title to that property is registered at HM Land Registry, that person’s obligation to make reasonable inquiries goes no further than to search the proprietorship register to ascertain the address of the registered proprietor.

It is the responsibility of the registered proprietor to keep his address up to date. If the person serving the notice has actually been given a more recent address than that shown in the proprietorship register as the address or place of abode of the intended recipient of the notice, then notice should be served at that address also.

My analysis of the Tanna case in party wall terms is available from the Party Wall Academy website at https://bit.ly/2q5L0DV